Otaru’s people are central to the story of the city and its transformation from a fishing village to a major shipping hub and now a national leader in heritage preservation.

Starting with the fishermen who moved to this northern outpost to make their fortunes from herring in the nineteenth century, Otaru has been driven by a pioneer spirit.

The proletarian writer Kobayashi Takiji (1903–1933) spent his youth in Otaru and set his novels and short stories in the city. He described it as “the heart of Hokkaido.”

Kobayashi saw Otaru as the center of Hokkaido’s power, a port from which resources from the island’s vast interior were shipped throughout Japan and to the world, and a destination for the steady flow of settlers seeking to begin new lives.

As fishing methods improved, the annual herring catch increased. In 1897, it was close to 100,000 tons. Sometimes the whole community helped to land the fish on the beaches. Local accounts from the mid-twentieth century recall days when the herring catch was so large that schools would close for the day, so that the teachers and parents of school children could help transport the herring.

Fishing families amassed wealth and built grand mansions in Otaru, furnished with the latest goods from Osaka, Kyoto, and Tokyo. They frequented luxury restaurants and fine art stores in the city.

Between 1869 and 1926, some 2.27 million people from other parts of Japan moved to Hokkaido to make their fortunes, and many landed at the port of Otaru. Some settled there, and by 1920 Otaru had grown from a fishing village to a thriving city of over 100,000.

Japan’s top architects made the banking district around Ironai Street a showcase for modern architecture. In the 1930s, the street was lined with an impressive mix of Renaissance Revival, Art Deco, and early Modernist buildings. The local government invited Japan’s leading civil engineers to design modern infrastructure for the city, including breakwaters, waterworks, canals, and public parks that are still in use today.

A grassroots citizens’ movement arose to protect the canal, which was seen as a symbol of the city’s former glory.

After years of debate, the city authorities modified the plan. Part of the canal was reclaimed in the 1980s, and a promenade was constructed along the remaining section of the canal to encourage people to return to the area. New businesses opened in the former warehouses, stores, and banks, and a burgeoning tourism industry developed to sustain the community and preserve the city’s heritage. The citizen-led movement influenced other cities across the country to consider how to balance development and preservation.

Starting with the fishermen who moved to this northern outpost to make their fortunes from herring in the nineteenth century, Otaru has been driven by a pioneer spirit.

The proletarian writer Kobayashi Takiji (1903–1933) spent his youth in Otaru and set his novels and short stories in the city. He described it as “the heart of Hokkaido.”

Kobayashi saw Otaru as the center of Hokkaido’s power, a port from which resources from the island’s vast interior were shipped throughout Japan and to the world, and a destination for the steady flow of settlers seeking to begin new lives.

Waves of prosperity

In 1865, Otaru was a fishing village of around 300 households. Fishermen moved to Otaru from southern Hokkaido, drawn by the large shoals of herring that spawned in the waters off the coast each spring. Processed into fertilizer for cotton and indigo, much of the catch was then transported by wooden merchant ships along the Sea of Japan coast to ports and wholesale markets in southwestern Honshu.As fishing methods improved, the annual herring catch increased. In 1897, it was close to 100,000 tons. Sometimes the whole community helped to land the fish on the beaches. Local accounts from the mid-twentieth century recall days when the herring catch was so large that schools would close for the day, so that the teachers and parents of school children could help transport the herring.

Fishing families amassed wealth and built grand mansions in Otaru, furnished with the latest goods from Osaka, Kyoto, and Tokyo. They frequented luxury restaurants and fine art stores in the city.

A growing port city

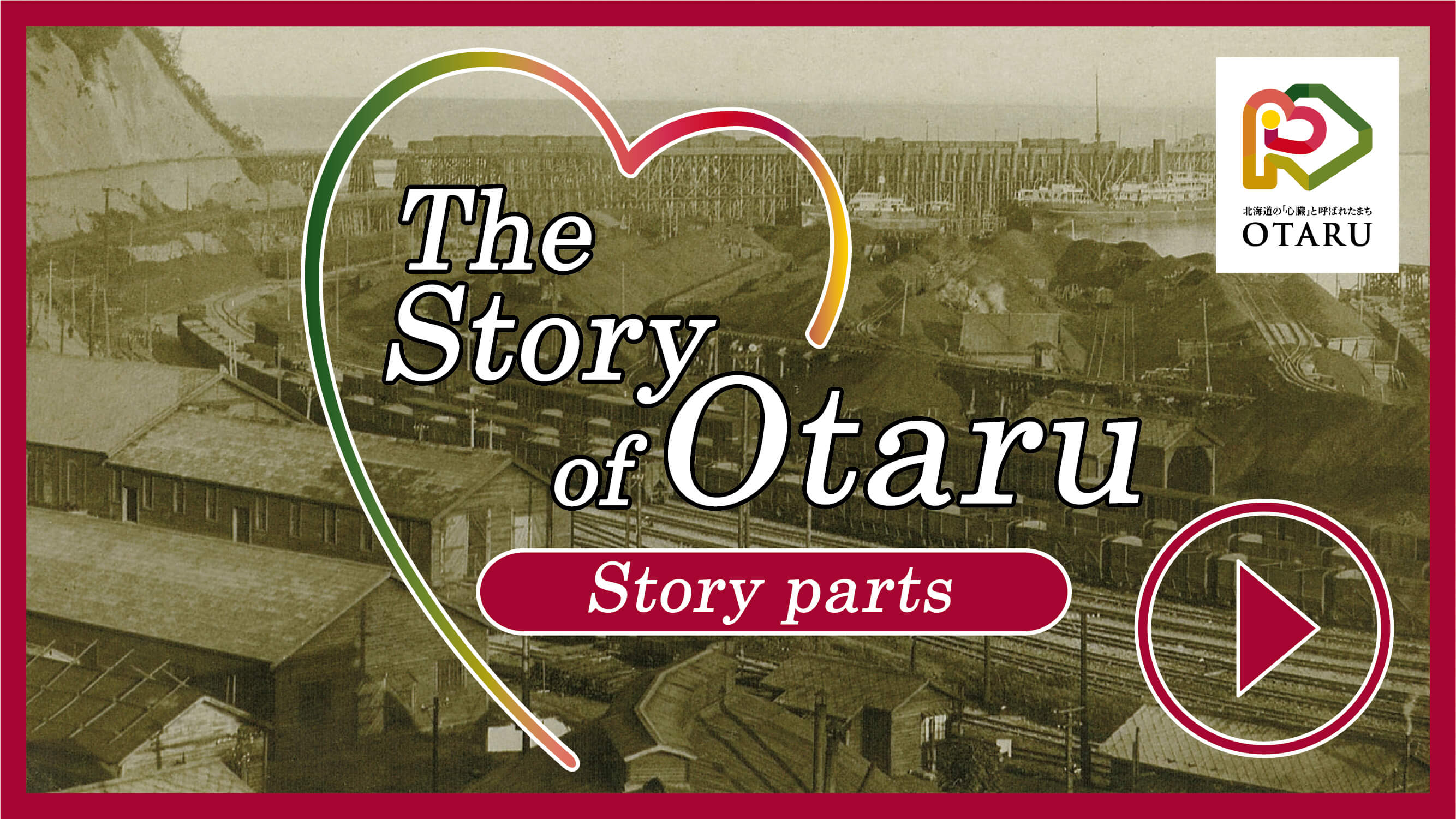

In the late nineteenth century, the Meiji government (1868–1912) resolved to develop and settle the resource-rich northern island of Hokkaido, and Otaru became a hub of the new frontier. In 1882, Hokkaido’s first railway opened to transport coal from inland mines to the port at Otaru, and the coal helped fuel the government’s industrialization drive.Between 1869 and 1926, some 2.27 million people from other parts of Japan moved to Hokkaido to make their fortunes, and many landed at the port of Otaru. Some settled there, and by 1920 Otaru had grown from a fishing village to a thriving city of over 100,000.

A booming economy

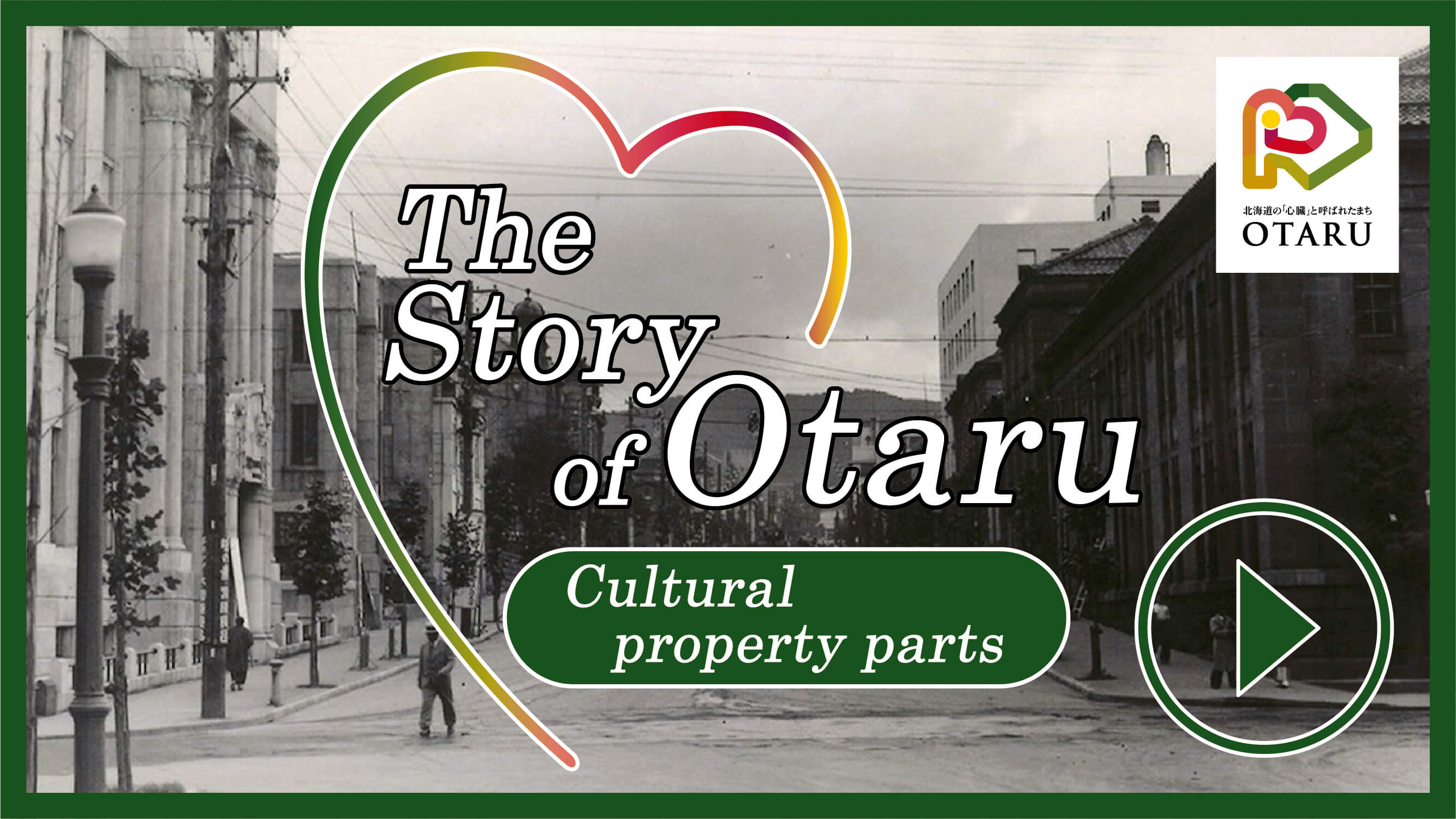

A new trade route to southern Sakhalin opened after the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), further elevating Otaru’s economic importance. Subsequently, branches of trading companies and banks moved to the city, hotels opened to accommodate international traders, and Otaru became Hokkaido’s financial center.Japan’s top architects made the banking district around Ironai Street a showcase for modern architecture. In the 1930s, the street was lined with an impressive mix of Renaissance Revival, Art Deco, and early Modernist buildings. The local government invited Japan’s leading civil engineers to design modern infrastructure for the city, including breakwaters, waterworks, canals, and public parks that are still in use today.

Turning tides

In the 1960s, the main source of the nation’s energy shifted from coal to oil, and Otaru lost its status as a major coal shipping port. In the same decade, a plan was proposed to reclaim the canal that had fallen into disuse, demolish warehouses, and build new roads.A grassroots citizens’ movement arose to protect the canal, which was seen as a symbol of the city’s former glory.

After years of debate, the city authorities modified the plan. Part of the canal was reclaimed in the 1980s, and a promenade was constructed along the remaining section of the canal to encourage people to return to the area. New businesses opened in the former warehouses, stores, and banks, and a burgeoning tourism industry developed to sustain the community and preserve the city’s heritage. The citizen-led movement influenced other cities across the country to consider how to balance development and preservation.

このサイトは「北海道の『心臓』と呼ばれたまち・小樽 」ページの英語版です。日本語版はこちら。

写真提供/小樽市総合博物館・中村憲様・運河画廊 藤森茂男の店

Images courtesy: Otaru Museum, Ken Nakamura, Gallery「Otaru canal Shigeo Fujimori」

Images courtesy: Otaru Museum, Ken Nakamura, Gallery「Otaru canal Shigeo Fujimori」